Bad things happen, it turns out.

There’s an endless rabbit hole on the Internet devoted to travelers debating whether or not you can get away with overstaying a visa for the Schengen Area, which is basically all the countries you’re most likely to visit while backpacking through Europe.

I’ll spare you the legalese and keep it short: You have 90 days to traipse your way from Italy to France to Germany and 23 other countries before you have to leave the area for a corresponding 90 day period.

You can probably guess that I didn’t follow the rule.

In my defense, not only was I a well-behaved tourist and avoided exploiting the free healthcare available to me, I also never stayed longer than 90 days in a row in Schengen. When I was finally caught by the British Home Office at London Stansted Airport in April, I had already overstayed my visa privileges by about 15 months.

While it was–begrudgingly–justifiable of the British government to refuse my entry into the UK based on my extended wanderings around Europe, my experience couldn’t be described any other way than kafkaesque.

I arrived at Stansted from Normandy, where I had spent the previous month volunteering on this awesome farm. My parents were arriving in London a day after me, and we were to spend the next ten days–my final days in Europe–wandering the city, plus a weekend in Cornwall, which I fell in love with last summer. And then I would finally go home, a little short of two years after I stepped on a plane from New York bound to Iceland.

When the immigration officer at Stansted opened up my passport and asked the first question, I knew I was fucked:

“When was the last time you were in the USA?”

“August 2013,” I replied.

Up to that point, I’d had no problems with customs officials anywhere in Europe. To name but a few examples, when I returned to Spain in April 2014 after spending a month in Morocco, the customs officer in Barcelona didn’t ask me a single question. Neither did the on in Rome on my inbound flight from Singapore (via Qatar) last November. Nor did the woman on the train that I took from Croatia to Budapest (Croatia is an EU member but not a signee of the Schengen treaty, whereas Hungary is) back in February.

But I hadn’t counted on the British taking their jobs too seriously, and I finally paid the price at Stansted.

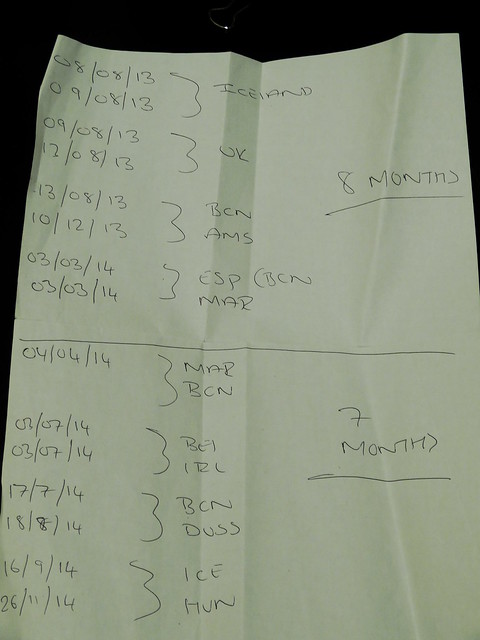

I was told by the customs officer to wait in a seating area cordoned off from the line of non-EU citizens queuing in line to have their passports stamped. A woman from Brazil was already waiting there; she said she was an au pair for an English couple, and despite having a UK work visa, this always happened to her. It was 11:30 AM when I first sat in the secondary waiting area, and about 1 PM when the officer came back. He was carrying this sheet of paper with a bunch of arithmetic on it and the names of the various places in the Schengen Area where I’d entered or exited.

I asked if I could speak to a lawyer, but because I was technically not on British soil, I had no right to one.

“We have decided it is necessary to interview you before making our decision allowing you to stay or not,” he said.

Then I was escorted into a part of the airport that most civilians probably will never see.

The officer who had originally examined my passport handed me off to a woman wearing a different sort of uniform; there was a neat Tascor logo stitched across the left side of her shirt. She led me through a door where a couple of security staff greeted her politely. This door was the first of many I would encounter in the next 24 hours that would require keycard security access.

After walking down a series of fluorescent-lit hallways–I wouldn’t see a window or the outside world for the next 12 hours–we stopped in what looked no different from your average corporate break room. A customs officer briefly checked my bag, then took my fingerprints. Apart from the first customs officer, every single person I interacted with, be it an employee of Tascor or a member of the British Home Office, was exceedingly polite. I was asked for the first time–but certainly not the last time–if I would like a cup of tea, or a sandwich.

Then I was ushered by a different Tascor employee into a different room with two desks, a telephone on the wall, and a couple of computer monitors, most of them displaying security footage of the room adjacent, where I would be held from 2 PM until midnight. My backpack and satchel bag were taken off of me, placed in huge transparent plastic bags, sealed with zip ties, and stowed away in a closet-sized space in the corner of the security room. I also surrendered my camera, laptop, and contents of my wallet, including my credit card (that last bit is important to remember), and asked to sit in a waiting room that looked like it belonged in a dentist’s office.

I was told to wait in a smaller room, barely large enough to contain a desk and a few chairs, and soon a black man and a white man entered. The black man spoke in a very heavy accent; if I had to guess I would say he was Nigerian. They didn’t wear name tags and when he told me his name it was unintelligible.

The Nigerian man was brusque but not impolite. He asked me how I had money to travel abroad for 20 months without going back home. I told him about my old job in Boston and how I had saved up money–approximately $23,000–before leaving to travel. I explained how in the past year I had started working as a freelance writer to replenish my bank account, and made it clear that I had never worked in the UK or anywhere else in Europe, which would be a violation of my tourist visa.

When I was asked why I was coming to the UK, I gave the same explanation as I had before: my parents had reserved two rooms at a B&B not far from Trafalgar Square, where would be staying for a week, before spending a weekend in Cornwall.

I showed them my reservation for a flight leaving 10 days later, from Luton airport to Boston with a stopover in Iceland.

I told them that on my three previous trips to the UK I had made friends who could vouch for me if need be–the problem here being that I had no way of contacting them, since I wasn’t allowed internet access.

“At this point I just want to see my parents and then go home. I’m done traveling for a while,” I said.

The Nigerian guy nodded his head, and he and the other guy got up and told me they would see what they could do. I went back to the waiting room and sat on a modern-looking red couch with fake leather upholstery. There was a TV mounted on the wall and a huge stack of DVDs, an assortment of current newspapers and slightly less current magazines, plus a small shelf filled with books. There were several travel guides sitting there, and a few gently used copies of the Koran. Two prayer rugs were rolled up next to the prayer books.

Down a small hallway was a bathroom, the room where I had just been interrogated, and another separate room labeled “FAMILY ROOM” in garish rainbow-colored Helvetica font. I peered in the family room, which had a small couch and a stack of children’s books, a few blankets, and not much else to suggest it was particularly family-friendly.

I felt a bit restless so I fired off a set of twenty pushups, then went over to the TV and flipped channels for a while. I helped myself to a packet of salt and vinegar crisps (or what we call potato chips in the USA), and killed an hour staring off into space.

At PM I was interviewed a second time by the Nigerian guy and his cohort, a chubby white bald dude named Kyle. The Nigerian rehashed the same sorts of questions, and then bizarrely asked me what I had been doing in the UK for the past 15 months.

As my passport stamps clearly showed, this was preposterous–I had barely spent a cumulative two months in the UK.

“We don’t know for sure that you left,” was his reply.

I explained in the least passive-aggressive way possible that not only do passport entry stamps mean that someone has entered another country, but that I would be happy to show him my blog and all the other places besides the UK that I had visited.

Except then I remembered that there was no internet access, and the absurdity of the situation engulfed me. I was screwed, so I started laughing.

“My parents just wanted me to go to law school,” I gasped between breaths.

Nigerian dude didn’t think this was funny, but Kyle did, because he chuckled a bit. He got the evil eye from his colleague for that.

I realized that bursting into laughter in the face of stern authority figures was probably not going to get me anywhere, so when they excused themselves I resigned myself to the certainty that I was probably not going to be invited into the UK. I put 8 Mile into the DVD player and watched it for the first time in years; it was even better than I remembered it being.

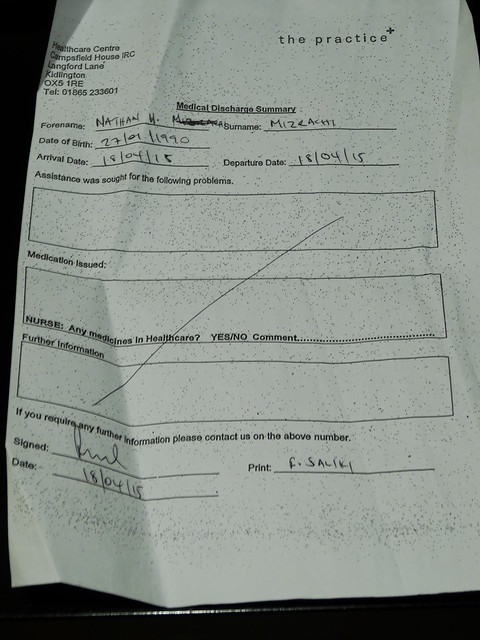

Going without exposure to direct sunlight or fresh air for the better part of six hours was driving me stir crazy, and things didn’t get any better when the Nigerian guy came back into the room and gave me the bad news I had already made my peace with. He handed me this sheet of paper explaining that the decision to deport me had already been made.

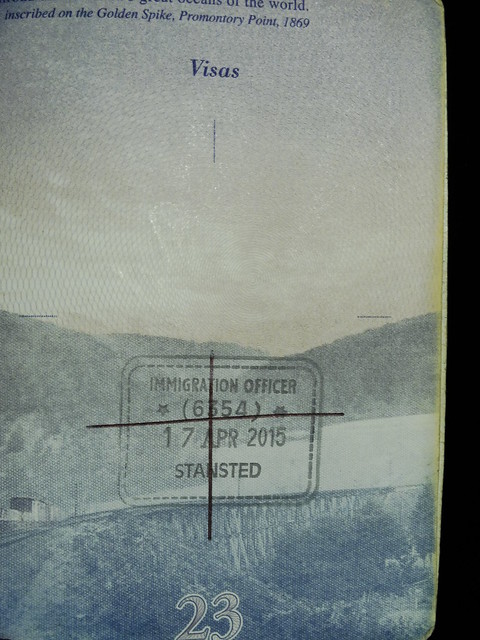

Then he mumbled something about following protocol and that I shouldn’t have stayed in the Schengen Area for so long, and then left. Also, my passport got a nifty looking reject stamp:

At this point it was time to let my parents know what was going on. I asked one of the two Tascor staff on duty if I could make a phone call, and they let me into their security room to borrow the phone there and dial out to the US.

It’s a credit to my dad–and a testament to the stupid shit I’ve done on my travels–that he didn’t freak out when I told him what was going on.

Apart from telling me that my stepmother was going to be disappointed at not being able to see me, and now having to cancel the reservation for my room in their B&B–it was fully refundable, thankfully–he was pretty cool about it.

“How are they treating you?” he asked me.

“Well, I’ve been offered biscuits and tea.”

“Go figure,” he replied.

Before I hung up the phone, I asked my dad to pass along the news of my detention and imminent deportation to my brother Eli to relay to our mutual friend Michelle, who had originally planned on hosting me for the night at her apartment in south London. At this point, given that there had been nothing but silence on my end of things for a good 6 hours (remember, I had no access to the Internet), I figured she must have been wondering what in the hell was going on.

I still had five hours to kill before I was to be removed from Stansted Airport and taken to a minimum security corrections facility (aka, jail), where I would be spending the night. So I amused myself by watching another movie, ordering food from the Tascor people (I was allowed as many microwave dinners as I pleased), and napping on the couch.

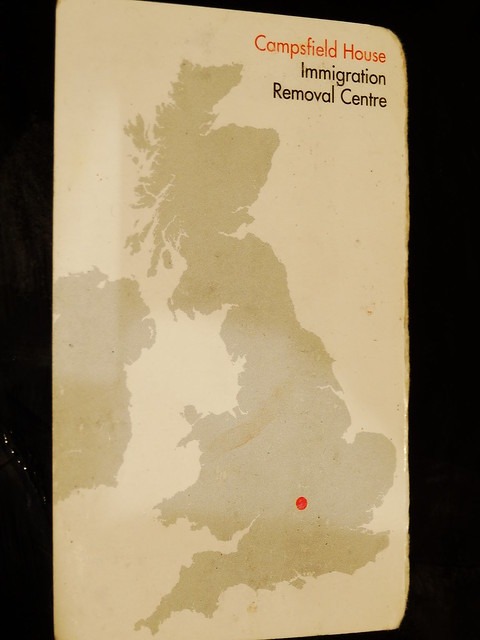

Finally, the moment arrived for my extraction. It was 11 PM. The door to the security room opened, and the two Tascor workers on duty told me that they were going to escort me through the public areas of the airport and transfer me to two other people waiting in a secure van, who would then drive me three hours north of Stansted to a place called Campsfield House Immigration Removal Centre. In case that mouthful of words is too much to handle, they were taking me to a minimum-security prison.

What happened next was the most undignified moment of my entire experience. I was told by one of the Tascor employees, a woman with her hair in a ponytail, that they would be handcuffing me before I was lead out through the terminal. This was for my safety as well as the safety of everyone else around me, she said, in the event I decided to run for it or do something crazy.

Neither she nor her cohort, a chubby bald guy (are all men employed by the British Home Office overweight and bald? What gives?) appeared to be carrying weapons. So it seemed like if they were tasked with handling potentially dangerous people, they would at least be better equipped. I pointed out that not only was I extremely mild-mannered and had no intention of posing a flight risk to either of them, but that I hadn’t been convicted of any sort of crime, and furthermore, if I was deemed safe enough to put on a commercial flight for my removal the next day, surely I could be trusted to walk un-handcuffed for three minutes through a relatively sedate airport concourse just before midnight.

My arguments fell on deaf ears. The Tascor lady did suggest I write out an official complaint form–I did, and then placed it in the sealed complaints box, making sure to clearly print out my email and other contact information.

It’s been over just over five months since I filled out that form and I have yet to receive word from Tascor or a representative of the British government.

The walk through the airport wasn’t too awkward. Most of the flights for the day had already landed or departed, so there weren’t many people around the terminal. No one seemed to notice that a handsome man wearing a green tweed jacket and torn up jean shorts was being escorted by two official-looking people with handcuffs around his wrists. We went out to the arrivals deck on the second floor of the airport, where a plain white transport van–the kind that plumbers or others tradespeople drive–was parked.

My bags were placed in the fenced-in rear of the van, while the sliding passenger door revealed a couple rows of hard, simple bench seats to sit on. My handlers–Tascor, not Home Office–asked me, as had those back in the airport, if I was OK. I quickly got the sense that this was an essential part of Tascor training.

“Are you OK?”

“Doing alright?”

It’s a clever, subtle way to greet someone who’s most likely not feeling OK, because when you’re asked this sort of question you automatically, after years of social training, tend to respond in the affirmative no matter how complicated the answer is. And if you choose to answer in the negative, there’s usually very little that people at this level of the chain of command can do for you anyways–apart from offer you a bottle of water or a sandwich, which they did with gusto. But it absolves them of feeling like they haven’t done enough to take care of you, makes you feel like they’re trying–even superficially–to take care of you, and in turn that makes you feel a little bit guilty for resenting them, like you’re ungrateful for their care. Strange how even for such a short time as I was incarcerated, I noticed this sort of power dynamic playing out.

I chose to wear my winter jacket, complete with detachable hoodie, over my head despite the relatively warm temperature, because they kept the lights blazing despite it being late at night. When we arrived at Campsfield House–which made national news in the UK back in 2010 for alleged mistreatment and unwarranted detention of detainees–it was 1:30 AM and I was sweaty and exhausted. I was asked to wait by the Tascor employee who drove me to Campsfield while she filled out paperwork with another Tascor employee at the detention center, and closed my eyes for around half an hour while the two of them schmoozed and prepared for someone else to be transported.

Being stuck in detention limbo gave me pause to wonder how, at any moment in just about every country around the world, including the USA and the UK, there are tens, if not hundreds of thousands, of more or less harmless people (specifically, those incarcerated by draconian mandatory drug sentencing laws) shuttled cross country at odd times of the day and night. The endless hours trickle by as reams of paperwork are filled out and the inmates stew until their minds are numb from boredom.

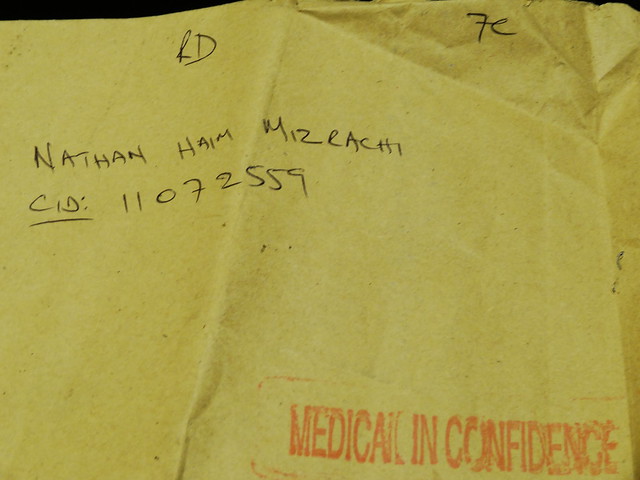

Finally I was called in to the reception area and given a cell phone, a £5 note to pay for a SIM card for said phone, and the briefest of medical exams. A bleary-eyed on-call doctor took my blood pressure and pulse, asked me to open my mouth and say “ah,” and asked me some basic questions about allergies and family medical history.

I was given a clean bill of health, then escorted by one other Tascor employee to my room. I was told that I could take my belongings in, but told that they could easily be stolen or I could be bullied into giving someone else my possessions, so I left them in the care of the Tascor employee.

One way that Campsfield House felt different from a traditional prison is that there were no cells. Instead, there were austere dormitories not unlike a cheap hostel. The lack of a lock on the door, not to mention the thick steel bars over our window–a full-sized one, not just an arrow slit–and the hulking 20-foot barbed wire fence just beyond the window were, however, clear reminders that this was no sleepaway camp. I was given a towel, clean sheet and blanket and crawled into bed; my three other roommates (all men) were already fast asleep.

I woke up about four hours later, at 7 AM, with golden light pouring in through our window. I grabbed my towel and walked down the hallway, which had blue linoleum floors, to find the bathroom. Toilets were located separately from showers, which unlike prisons in movies, were in private stalls. Mine had a lock–I’m guessing that showers in higher-security prisons don’t give off that sort of privacy. The water was warm enough, and I actually felt pretty close to normal at that point.

I still had an hour and a half to kill before another van would come to collect me and shuttle me back to Stansted Airport, so I went to the cafeteria for breakfast. Breakfast at Campsfield house consisted of flavorless oatmeal porridge, white bread toast with grape jam (the kind made almost entirely from synthetic ingredients), and a hard-boiled egg with a yolk that was almost green. I put a generous layer of brown sauce on my piece of toast and then spread some of the egg white on top, but despite being hungry I didn’t have the appetite for this sort of food.

A gangly young Afro-Caribbean guy with a teardrop tattooed beneath his left eye walked by and grinned at me.

“You don’t like the food here?” he asked.

“You could tell from my face, couldn’t you,” I replied.

“I just got transferred from another prison to here for good behavior.

The food here is pretty good compared to what I had before.”

Hearing that from someone who was actually serving time–it turned out his name was Carlos and he’d been serving close to a year in a medium-security prison for “selling stolen goods” (I didn’t ask him to specify what sort of goods)–made me realize how soft I was. Carlos told me that he planned on moving to Portugal to live with a cousin there and get away from the gangs that plagued his East London neighborhood. I told him not to worry, the Portuguese spoke excellent English.

There was a small courtyard for the detainees to hang out in, and with the sun already up and the sky clear and blue, it seemed like a good idea to go out. A solid cluster of men congregated about the courtyard; there was a slight majority of Afro-Caribbean men, as well as a sizeable number of men from India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Vietnam (I’d seen one group of three Asian men pouring Vietnamese fish sauce onto their porridge, so I assumed that’s where they were from, but I could be wrong). There were also two or three Polish men smoking in one corner of the courtyard, and I could see a few turbaned Sikhs or Hindus sitting cross-legged through the barred windows of a prayer room on the other side of the courtyard.

For a little over an hour I walked in a large, slow circle around the courtyard; finally, one of the officers on duty–this one wasn’t Tascor–told me that my ride to the airport was here. This time three people from Tascor picked me up. One of them was a tall black man; he told me his name was Richie, and when he asked me how I was feeling, I was honest with him.

“I’m tired and kind of bummed out this happened. I was supposed to be meeting my parents today–we were going to London for a holiday.” First world problems, I guess. But Richie sympathized.

“Before you get back on that plane you need to ask an [immigration] officer if there’s any way you can have your ruling overturned. Maybe they can issue you a temporary visa to stay instead.”

Three hours later, Richie and the two other employees were leading me through a packed terminal, bypassing the normal security checks and handing me off to another Tascor employee, who would be escorting me on my flight to France. Unlike the night before, this time I was not handcuffed. I asked Richie why not.

“Since there’s three of us here instead of just two like yesterday, we’re not required to handcuff you. It’s a bit humiliating, isn’t it?”

I wanted to give this guy a hug, but restrained myself. I’m glad that at least one of them recognized the indignity of treating me like a dangerous criminal. Richie shook my hand and wished me luck before I walked down the concourse.

As I boarded the plane the Tascor employee escorting me handed a brown envelope containing my passport to the head stewardess. She was instructed to give it directly to the French customs agent at the airport we were landing in.

This begs the question as to why I was being flown to France, and not just deported to my country of birth? Apparently, the rules stipulate that an illegal migrant or traveler denied entry must return to the country that they just came from. You might guess I was being flown to Paris or some other major French city–nope, that wasn’t the case. My destination aboard Ryanair flight FR8868 was Tours, located in central France and near the Loire Valley. If the English had wanted to deport me to the American equivalent of Tours, they probably would’ve sent me to Fargo.

I arrived in French Fargo and was told by the crew to wait while the rest of the passengers deplaned onto the tarmac. Tours is a small city, and its airport didn’t have a single gate; just one grocery store-sized building with a waiting area and one customs booth to stamp passports. Apparently I wasn’t high-profile enough to warrant proper notification of the authorities, so it took the police about five minutes to show up at the bottom of the steps of the plane. None of them spoke English or Spanish, so I made do in my very rough French and explained that I had been deported. None of the three officers, I should add, were even gendarmerie; they were simply small potatoes police.

I was probably the closest thing to an international criminal that they’d ever encountered.

When I approached the customs booth, the police escorting me explained to the woman behind the desk–also police–that I had been detained by the British and sent back to France.

“Pourquoi ont-ils vous envoient ici?”

“Pourquoi je suis dans l’zone du Schengen pour beaucoup temps. Parles vous anglais ou espagnol?” I asked.

If you speak French and realized what I said sounded a bit unorthodox, now you know what a fool I must have sounded like to them.

The passport control lady told me to hold on; a few minutes later, a civilian employee who appeared to work at the tourist office desk in the airport walked over. She spoke perfect English with an Irish lilt.

I told the French-Irish woman how I had been interrogated, detained, and ultimately deported to France by the British because of the technicality that I stay outside the Schengen Area for 90 days.

“I’m just a tourist,” I added.

After a brief back-and-forth, my passport was stamped just as it had been on every other occasion that I entered the Shengen Area. The police asked me where I would go now.

“To Caen, to the farm where my friends are,” I replied.

Caen was about 260 km north of Tours. They asked how I would get there. Did I need money for a train ticket? After my ordeal of the past 24 hours, I was sorely tempted to say yes, but that would have been disingenuous.

“Non, je fete le auto-stop (hitch-hiking),” I told them, holding out my thumb. At this they laughed. The Irish woman insisted I take two water bottles and a Google map of the main highway going north. She also drove me in her car 10 km north of the airport to the main road, saving me the trouble of walking there myself from the airport or taking a bus. I thanked her profusely as I got out of the car, gave her a hug, sat my bags down by the side of the road, and my stuck my thumb out.

Five rides, 260 km, and six hours later, I arrived in downtown Caen almost 36 hours after I left the city to fly to London. My friends had driven into the city center from the farm, and I couldn’t have been happier to see them; I felt relieved to be in a place that at that point felt like home.

THe Aftermath

A few things happened after I was deported back to France. Originally, I wondered if I had endured interrogation, imprisonment, and deportation entirely on the British government’s dime. I checked my credit card and saw a charge of $272 for the airfare from Stansted to Tours–barely an hour’s flight on the cheapest budget airline in the world? I called my bank and tried charging it back, but that proved to be impossible.

My dad and stepmom cancelled my hotel room in London as well as our weekend cottage rental in Cornwall, instead coming to Paris for an overnight. What with the rain, our swanky hotel in my favorite neighborhood of Saint-Germain-des-Pres, the Michelin-starred meal we ate within view of the Eiffel Tower, and a quick peak into the Musee d’Orsay, there was a silver lining to what could have been a complete disaster.

And then, ten days later, I flew back to London–holding my breath as I waited in the passport line, wondering if I would be rejected again–was issued a 24 hour transit visa after a nervy 30-minute wait in secondary inspection, and then finally made it back to the good ol’ US of A on May 1st.

I hope the next time that I deal with the British Home Office, whoever is inspecting my passport has just a little bit more of a sense of humor and perhaps a more liberal interpretation of the law. As we’ve seen with the current refugee crisis, borders are not just an annoyance for tourists like me; they mean life and death for people who genuinely require safe entry.

Sorry to here about all the crap the UK twats gave you Nathan.I left there nearly 30 years ago and would never return. I hope you continue to write a blog and post it as usual.

All the very best to you. Martin.

Thank you Martin! To be honest, the USA border control is no better–my non-American friends have told me some horror stories.

I’m British and … well … I’m almost not surprised! Sorry it was such an awful hassle for you – but at least you managed a fantastic story out of the experience! 🙂

You know Swebb, I was thinking that exact same thing while it was going on: at least I was going to get a good story out of it 🙂

The British attempted to deport me once… I somehow talked them into allowing me 1-month entry, but they took my passport. I arranged for a friend who helped me deal with the Home Office and after an interrogation a month later I got my passport back and been here ever since… The best part of 15 year. Great story, after something like this though I would never want to return to the UK, how do you feel? Would you and have you? Funnily enough the British public are adamant that there borders are just wide open and everyone walks in and out as they please. All Brits who think that should read this story.

The Home Office is pretty nasty, isn’t it!

This story has just made me laugh a little though I know how it feels I went through the same shit when I was coming in France and now am stuck here coz I don’t know how to escape the that deportation and I don’t want to be in that waiting zone “kind of prison” again. But you are lucky you can now travel freely.

Oh shit! Well, this time what I would suggest doing is avoiding the UK at all costs. Perhaps also consider taking a break from the Schengen before trying to return to your home country — go to Croatia, or Morocco, or Turkey for a while.

Really interesting report!

I’m an migration lawyer In Spain. And I find your story truly informative. The are huge differences between within EU members’ migration law. For example in Spain you do have the right of be assist by a lawyer at the airport.

Thanks for sharing your experience!

Thank you Patricia! The British were awful. I’ve made sure that when I went back to the UK to enter via Ireland. Even then I had problems, but the customs officer at the Dublin airport was much more reasonable, and after thirty minutes’ wait she let me through the border.

Anyways now that Brexit has happened, I’m guessing it will be even more difficult for non-British nationals to enter the UK.